Vi bjuder regelbundet in ledande entreprenörer och investerare att dela med sig av sina erfarenheter och sin expertis till Stripe Atlas Community. Andrew Chen är generalpartner på Andreessen Horowitz, där han investerar i konsumentstartups. Tidigare ledde han Ubers passagerartillväxt, med fokus på förvärv, ny användarupplevelse, bortfall, meddelanden och e-post.

Varför marknadsplatser

Andrew Chen har goda skäl att vara optimistisk när det gäller marknadsplatser. Strax efter att ha gått med i Ubers tillväxtteam nådde företaget sin högsta tillväxttakt på flera år. Vid den tiden hade det registrerat över hundra miljoner människor och spenderade nästan 1 miljard USD på sina tillväxtinsatser årligen. Det tog företaget fem och ett halvt år att nå en miljard resor, men sex månader senare hade man nått två miljarder resor. Den här accelerationen och skalan skulle motivera vilken yrkesperson som helst, men den gjorde honom lika fascinerad av marknadsplatser som kategori som av Uber som företag. I sitt första stora inlägg efter att ha börjat på Uber tänkte Chen så här:

Utifrån en UX-upplevelse är Uber som att trycka på en, så kommer en bil, men ur ett affärsperspektiv är det en stor samling av hundratals hyperlokala marknadsplatser i nästan 70 länder. Varje marknadsplats är tvåsidig, med förare och passagerare, och har sina egna nätverkseffekter som drivs av upphämtningstider, täckningsgrad och användning.

Flera år senare betraktar Chen sig själv som investerare, rådgivare och fortsatt student av marknadsplatser. ”Under det senaste decenniet har många av de mest framgångsrika företagen – Airbnb, Uber, Etsy – varit marknadsplatser. Och om man tittar på den övergripande kategorin finns det också eBay och företag som har utvecklats till marknadsplatser som Amazon”, säger Chen. ”Marknadsplatser är den enskilt mest övertygande sektorn under de senaste decennierna och bland de bästa sedan internet började. Jag vet att det är högt ställda förväntningar, men som kategori kan marknadsplatserna nå – och har nått – nya höjder.”

Chen har skrivit mycket om marknadsplatser och ett drag som gör dem särskilt kraftfulla: nätverkseffekter. Detta är fenomenet att nätverket blir mer värdefullt för användarna i takt med att fler människor använder det. Som många nystartade företag bevisar är nätverkseffekter inte exklusiva för marknadsplatser online, men som affärsmodell har marknadsplatser i sig fler hävstänger inbyggda för att driva nätverkseffekter. Enligt Chen finns det fyra hävstänger för nätverkseffekter som är centrala för marknadsplatser:

- Produktreklam = marknadsplatsreklam: ”En marknadsplats är i grunden en onlineplattform som gör det möjligt för säljare och köpare av varor och tjänster att komma i kontakt med varandra och göra affärer. Oavsett om du säljer Pez-dispensers eller trädgårdstjänster på en marknadsplats marknadsför du var du säljer lika mycket som vad du säljer”, säger Chen. ”Med andra ord, ur ett användarförvärvsperspektiv uppmanas säljarna att marknadsföra att de använder plattformen. I processen skapar marknadsplatserna en viral loop som genererar gratis, organisk trafik.”

- Gemensamma upplevelser > samma upplevelser: Säg att du använder en smartphone. Du kanske har samma produktupplevelse som miljarder andra människor, men det är inte en delad upplevelse. ”På marknadsplatser kan du uppleva marknadsplatsens produkt tillsammans med andra användare. Nätverkseffekter blir i allmänhet starkare ju mer produkten eller tjänsten upplevs samtidigt och på samma plats”, säger Chen. ”Homesharing och ride-sharing är perfekta exempel. Om du tar en bil eller hyr ett hem med en vän har du inte bara upplevt produkten, utan också upplevt produkten tillsammans. Relationen till en marknadsplats smälter samman med relationen till vännen. Det här är en typ av nätverkseffekter som verkligen blir bestående för marknadsplatserna.”

- Gemensamma upplevelser > egna upplevelser: ”Marknadsplatser bygger på det faktum att många föremål som vi äger är underutnyttjade. Kärnan i den principen är tron på att dessa föremål är bättre att dela än att bara äga för sig själv”, säger Chen. ”Det finns till exempel ett företag som heter Hipcamp som hjälper friluftsmänniskor att hitta campingplatser, inte bara i offentliga parker utan även på privat mark. Genom att äga egendom har markägare också kostnader, från skatter till underhåll. Genom att göra sin ägda tillgång till en delad tillgång kan de få ut mer värde av marken genom att dela den med människor som får njuta av den och respektera den.”

- Fler användare, bättre produkt: ”För många företag kan det innebära en kvalitetsförsämring när fler användare ansluter sig. Det kan vara svårare att anpassa sig till större volymer och fler användningsområden. Men marknadsplatser är en sällsynt typ av företag där ju fler som använder produkten, desto bättre blir den faktiska upplevelsen”, säger Chen. ”Ta Wonderschool, en marknadsplats för daghem. Ju fler daghem det finns, desto fler föräldrar kan hitta alternativ som passar just dem när det gäller variation – som Montessori eller språkskolor – och närhet till hemmet. Föräldrarna blir mer entusiastiska och engagerade i tjänsten, vilket hjälper daghemmet att hitta och skaffa fler kunder.”

Den mest underskattade aspekten av marknadsplatser

För Chen är den mest underskattade egenskapen hos marknadsplatser deras förmåga att facilitera tjänster. ”Som bransch har teknik gjort bra ifrån sig när det gäller att få saker från punkt A till punkt B. Användare på Amazon, eBay och Shopify kan få hem en produkt till dig på en vecka, en dag eller ibland i realtid”, säger Chen. ”En punkt där marknadsplatser inte har varit bra – men borde vara det – är inom facilitering av tjänster. När det är dags att hitta en barnflicka till våra barn eller en coach att anlita, frågar vi fortfarande oftast vänner och kollegor om referenser. Marknadsplatser är dock väl rustade för att facilitera tjänster eftersom de kan bidra till att standardisera upplevelser – och i vissa fall till och med produktifiera dem. Vi har sett hur marknadsplatser hjälper främlingar att dela hem och bilar, men det gäller inte alla tjänster ännu.”

”De flesta marknadsplatser kommer behöva ändra sin strategi för att nå dit. När de gör det kommer de att få tillgång till en enorm global marknad, en marknad som bara i den amerikanska ekonomin omsätter flera biljoner dollar. För att göra det måste marknadsplatserna möta användarnas förväntningar på kvalitet och förtroende. Men vad innebär det egentligen?”, säger Chen. ”Kvalitet och förtroende kommer när man ger en konsekvent upplevelse. På köparsidan innebär det bland annat att man skapar en heltäckande ontologi över alla erbjudanden, har försäkringar, utbildar säljare och skapar servicenivåer. På säljarsidan handlar det om att utrusta säljarna som småföretagare. Användarna bygger nu upp hela företag på marknadsplatserna, och de behöver göra allt mer på dem. Marknadsplatserna måste hjälpa säljarna att prissätta produkter och tjänster, utbilda och hantera personalstyrkan, skaffa verktyg för att hitta leverantörer och implementera CRM-system för att hantera leads.”

Marknadsplatser utvecklar ett djupt symbiotiskt förhållande med de företag som byggs upp ovanpå dem. ”Ta en hamburgerkedja som är listad på Uber Eats. På egen hand kan den förlita sig på fottrafik, lokal reklam eller organiska rekommendationer. Men världen håller på att förändras. Antalet nedladdningar av matleveransappar har ökat med nästan 400 % jämfört med för tre år sedan. Den här trenden förändrar hur restauranger får intäkter och till och med hur utformas”, säger Chen. ”Om hamburgerkedjan inte fanns på en marknadsplats som Eats skulle den behöva bli expert på att utveckla en app och få användare att ladda ner den med syftet att växa bortom en lokal grupp återkommande kunder. Men på en marknadsplats kan hamburgerkedjan betjäna en bredare publik. Till exempel kan man fånga upp användare som kanske är sugna på pizza eller falafel och övertyga dem om att äta hamburgare istället.”

Det är inte bara restaurangerna som drar nytta av detta förhållande. ”Marknadsplatser som Eats är starkt beroende av restauranger som är mycket professionella vars verksamhet redan är igång och som redan har ett eget varumärke. Dessa restauranger är ofta de som folk föredrar att beställa från mest och de befinner sig i ’toppen’ av power law-kurvan”, säger Chen. ”Matleveranser är bara ett exempel, men samma dynamik har spelat ut sin roll i allt från korttidsboenden – med marknadsplatser som Sonder och Lyric– till lokala serviceföretag som listas på Thumbtack eller Care.com. Sambandet mellan marknadsplatser och deras professionella utbud är en av de mest ömsesidigt fördelaktiga relationerna i hela teknikbranschen.”

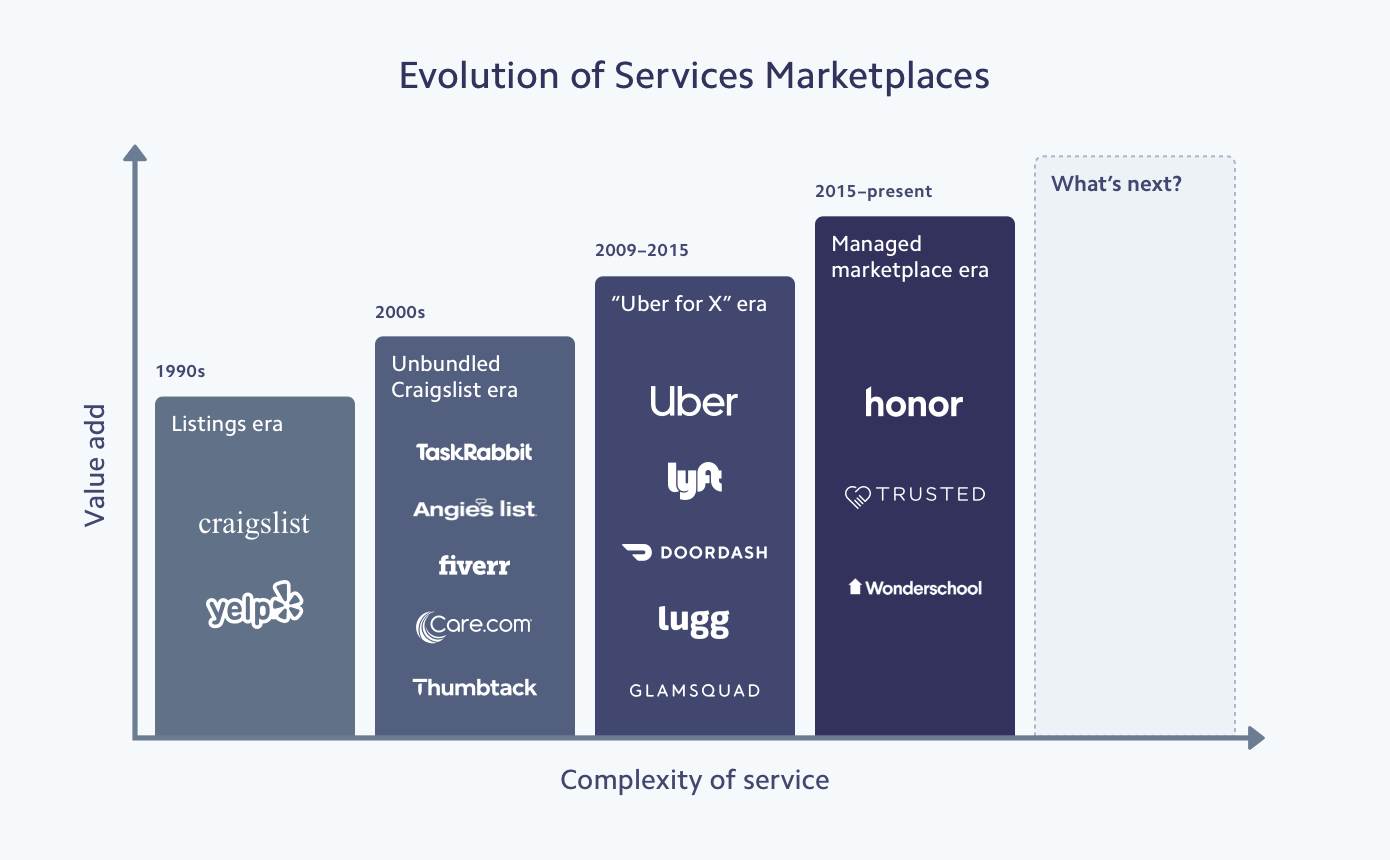

Enligt Chen är övergången till att facilitera tjänster inte bara en möjlighet för marknadsplatserna, utan också en eventualitet. ”Det finns fortfarande en långvarig tro på att de flesta marknadsplatser bara är uppiffade versioner av Craigslist-kategorier. Man menar att man, för att bygga en marknadsplats, bara behöver ta en Craigslist-kategori och göra den bättre. Det kan ha varit sant för tio år sedan, men det har förändrats”, säger Chen. ”Som investerare anser jag att marknadsplatser är spännande när grundarna tar ett licensierat yrke från tjänsteekonomin och bygger en marknadsplats kring det. Det handlar inte bara om en snygg annons som en säljare lägger upp och en köpare klickar på. Kanske finns det en video som hjälper användarna att förstå och visualisera tjänsten de är på väg att få. Eller ett betygssystem som går djupare än systemet med 1–5 stjärnor som vi alla känner till. Jag tror att den här typen av utveckling mot tjänster är en underskattad aspekt av att bygga upp en marknadsplats som inte får positiv uppmärksamhet på bloggar eller Twitter, men som är en av de viktigaste ingredienserna.”

Innehåll från diagram från Andrew Chen och Li Jin.

Den mest överskattade aspekten av marknadsplatser

Kärnan i ”Uber for X”-företagspresentationer är den mest överskattade delen av marknadsplatserna: den övergripande tron på att en marknadsplatsstrategi kan översättas till alla marknadsplatser. ”Miljarder dollar har förlorats för människor som beskrivit sin verksamhet som ’Uber för en annan bransch eller marknad’. Det är ett tacksamt sätt att beskriva ett företag, men det leder sällan till framstående marknadsplatser”, säger Chen. ”Livsmedelsbutiker. Samåkning. Hemuthyrning. Det har funnits framgångar i dessa kategorier. Men baksidan är också sann. Massage på begäran eller betjänter träffar inte riktigt samma sweet spot som marknadsplats. Du kan inte flytta över strategin från en marknadsplats till en annan utan att förstå grunderna till varför de här mekanismerna fungerade.”

Att återanvända en playbook från ett annat företag är en risk för alla typer av företag, men Chen ser att det händer oftare – och i högre utsträckning på fel sätt – med marknadsplatser. ”Låt oss ta två exempel relaterade till fordon: samåkning och parkering. Det visar sig att samåkning fungerar bra som en on-demand-marknadsplats eftersom det är en tjänst som du kan välja och använda nästan varje dag. Och inte bara för pendling, utan i allmänhet för att ta dig från punkt A till punkt B. Detta ökar likviditeten på marknaden”, säger Chen. ”Å andra sidan är parkeringstjänster begränsat till bilägare eller personer som hyr en bil, vilket är en mycket mindre marknad än personer som vill åka bil. Dessutom kommer du sannolikt att utföra tjänsten två gånger om dagen: vid avlämning och upphämtning. Från utbudssidan kommer människor inte att kunna försörja sig som parkeringstjänst på heltid.”

Slutsatsen är att många människor gillar att gruppera marknadsplatser som en sektor, när de i själva verket är mer olika än lika, enligt Chen. ”Det finns många nyanser med marknadsplatser. Men när det finns ett hett företag eller en het kategori försöker de flesta tillämpa alla mönster för att se vad som kommer ut i andra änden. Ibland fungerar det, men oftast gör det inte det”, säger han. ”Marknadsplatser utgör inte en sektor på samma sätt som spelande. Marknadsplatserna kan omfatta allt från hotellbranschen till transportsektorn, utbildning och rekreation. De tillhör alla distinkta branscher som inte så lätt kan anpassas till en marknadsplatsstrategi som passar alla.”

Knäcka kallstarten genom att utmanövrera Metcalfes lag

En av de största utmaningarna för marknadsplatser är hur man ska få ett nätverk att växa – och var man ska börja. Det kallas ofta för kallstartsproblemet. ”Om du minns dot com-bubblans historia, så tillskrevs många av de tidiga rörelserna inom teknik något som kallas Metcalfes lag. Den innebär att när du lägger till fler noder i ett nätverk ökar antalet sammankopplingar snabbt”, säger Chen. ”Om man ritar upp det i en graf ser det ut som en galen exponentiell tillväxtkurva. Det tyder på att det finns ett ”first mover advantage”, för om du rör dig snabbt och får noderna före alla andra kommer ditt nätverk att bli bättre. Dynamiken i den här lagen har blivit vanlig affärsrådgivning och en del av lexikonet för startups.”

Problemet är att det inte är det som faktiskt händer. ”Alla som arbetar med nystartade företag och marknadsplatser vet att det inte alls är så här det fungerar”, säger Chen. ”När ditt nätverk är någonstans runt nollan och densiteten eller storleken på nätverket som krävs för att ta fart, vill ditt nätverk självförstöra sig hela tiden. Om du inte lägger till nya användare – vare sig köpare eller säljare – vill ditt nätverk återgå till nollan. Dina köpare dyker upp och ser inte tillräckligt många för att köpa. Dina säljare ser ingen som budar och bestämmer sig för att flytta till en annan butik. Fram till dess att du kommer till ditt nätverks accelerationshastighet kämpar du mot anti-nätverkseffekter.”

Enligt Chen finns det många smarta sätt som grundare har knäckt kallstartsproblemet och framgångsrikt undkommit entropin i tidiga nätverk. Här är tre exempel:

Kommer in för verktygen, stannar för nätverket:. ”Hipcamp började som ett sätt att hitta offentliga campingplatser. De samlade in och indexerade campingplatser, så att människor kunde hitta dem på ett ställe. De sammanställde befintliga listor, så aggregeringen av utbudssidan var inte särskilt krävande”, säger Chen. ”Detta gjorde att Hipcamp kunde vara användbart som ett verktyg för köparsidan från dag ett, även om det inte var användbart som en marknadsplats från början. När det väl visade sig vara ett användbart verktyg dök efterfrågesidan upp – nämligen campare – och Hipcamp kunde satsa på en bokningsfunktion. Sedan började man fördjupa utbudssidan genom att registrera privata campingplatser och fastigheter.”

Chen krediterar medinvesteraren Chris Dixon som namngav den här tekniken. ”OpenTable är ett annat känt exempel på denna metod för kallstart. OpenTable startade på säljarsidan, som ett verktyg för att hjälpa restauranger att hantera bordsbokningar, och sedan började det driva efterfrågan. Hipcamp är ett bättre exempel på ett verktyg på köparsidan som sedan ökade utbudet som ett resultat av detta”, säger Chen. ”Det finns många andra exempel, men strategin är att skapa ett lagerhanteringsverktyg som ett mellansteg för att bygga en marknadsplats. Många gånger börjar det på säljarsidan.”

Digitalisera upplevelser med penna och papper. ”Pietra är en marknadsplats för specialtillverkade smycken. Några Uber-alumner startade företaget och är därför bekanta med dynamiken på utbuds- och efterfrågesidan. Deras idé är att processen för att köpa dyra smycken – från en produkt- och köpupplevelse – är föråldrad, särskilt för millenniegenerationen. För det första upptäcker man på olika sätt, sannolikt från Instagram-kändisar eller tillverkare som streamar om sina smycken. Och för det andra är smyckena inte personliga eller anpassade. Du kanske gillar en armbandsdesign men vill ha din födelsesten eller en gravering”, säger Chen. ”Pietra bygger en tvåsidig marknadsplats – eller tresidig om du inkluderar influencers – för kunder och tusentals juvelerare i mycket små butiker, som familjejuvelerare.”

Dessa mindre smyckesbutiker kan ofta göra specialtillverkade smycken till bättre priser än större kedjor, men deras backoffice är inte alltid effektivt. ”Det är mycket kommunikation fram och tillbaka som kan handla om preferenser kring stil, storlek och inköp. Pietra konsoliderar och sparar dessa specifikationer i en app med ett snyggt gränssnitt. På så sätt kan en liten juvelerare som kanske arbetar med 50 potentiella kunder inte missa eller förlora information”, säger Chen. ”Det gör processen enklare för både juvelerare och kunder. Och ur ett affärsmodellsperspektiv, med alla kundpreferenser samlade på ett ställe, blir det svårt att byta till en annan marknadsplats.”

Etablera en minimigaranti för utbudssidan. ”Många marknadsplatser – särskilt inom tjänsteekonomin – kan dra nytta av att börja med en garanterad grundlön tidigt i processen. Uber kan till exempel lova 25 USD/timme om en förare genomför ett visst antal resor per dag. Den här förutsägbarheten ger inte bara mer stabilitet till dem som arbetar på utbudssidan, utan hjälper också företaget att snabbt bygga upp utbudssidan”, säger Chen. ”Med den volymen på utbudssidan får man tillräckligt momentum för att bygga upp efterfrågesidan. När efterfrågesidan sedan byggs upp registrerar sig fler på utbudssidan. Nu snurrar svänghjulet. När marknaden når likviditet kommer intäkterna på utbudssidan – till exempel Uber-förare – börja närma sig garantin så att marknaden till slut stöttar garantin på ett naturligt sätt.”

Detta är en kraftfull teknik med tanke på hur många marknadsplatser som kämpar med utbudet. ”Jag tror att nästan alla de bästa marknadsplatsföretagen i slutändan är utbudsbegränsade i motsats till efterfrågebegränsade. Oavsett om det handlar om utbildning, matvaror eller äldreomsorg finns det i princip obegränsad efterfrågan, eftersom du kan hålla prisparitet med allt annat”, säger Chen. ”Och det som tenderar att hända är att man till slut ägnar mycket tid åt att tänka på utbudssidan. Jag märkte det här på Uber. När man lanserar stad för stad blir man väldigt fokuserad på utbudssidan av sin marknad – och samma utmaningar och idéer dyker upp om och om igen.”

Utbud-efterfrågan-utbud-utbud-utbud kontra efterfrågan-utbud-efterfrågan-efterfrågan-efterfrågan

Varje marknadsplats måste bedöma den relativa tätheten mellan utbud och efterfrågan och vilket nätverk som är bäst. Chen har observerat ett mönster för C2C-, B2B- och B2C-företag. Det handlar om vilken sida som kommer att uppleva högre friktion vid registreringen, vilket ofta motsvarar vilken sida som kommer att göra mer arbete.

C2C och B2C: ”På en konsumentmarknad som samåkning arbetar en förare flera timmar per dag, medan passagerarna kanske tillbringar 15–20 minuter i bilen. Eller om du är en marknadsplats för barnomsorg och förskoletjänster som Wonderschool, måste företagen skaffa licenser, medan familjer främst behöver registrera sig för att delta”, säger Chen. ”Utmaningen med dessa marknadsplatser brukar vara att få tillräckligt många leverantörer att delta, eftersom de måste göra mer arbete för att vara med. Så med konsumentorienterade startups, börja med utbudet och sedan efterfrågan. Sedan ska man fokusera på utbud, utbud, utbud.”

B2B: ”Den vinnande ekvationen för B2B-marknadsplatser är det omvända. Ta lastbilsföretag som Convoy eller en marknadsplats för lagerhållning som Flexe. Dessa typer av företag tenderar att vara mer efterfrågebegränsade, eftersom din efterfrågesida sannolikt är Fortune 500-företag. Efterfrågesidan är mindre intresserad av prissättning och mer av kvalitet och rykte. Försäljningscykeln är lång. Nystartade företag på marknaden kommer att närma sig dessa företag, erbjuda en tjänst och få LOI:er. De kommer att använda dem för att skaffa finansiering och få utbudssidan på plats. Sedan går de tillbaka till att sälja till Fortune 500”, säger Chen. ”Jämför detta med marknadsplatser för konsumenter, där konsumenterna är priskänsliga. I det fallet, om du någonsin har ett för högt utbud, kan du alltid sänka priserna, och efterfrågan kommer att skjuta i höjden. Och sedan kan du balansera din marknadsplats igen. Men det är tvärtom med B2B-marknadsplatser. Fokusordningen blir i slutändan efterfrågan, utbud, efterfrågan, efterfrågan, efterfrågan, efterfrågan.”

En varning: Naturligtvis är dessa mönster tumregler, det finns andra faktorer som spelar in. ”Det finns säsongsvariationer och regioner. I Las Vegas fanns det till exempel ofta ett överutbud av samåkning eftersom det finns fler förare – och många åkare tog taxi. I San Francisco eller New York var utbudet av samåkning mer begränsat. Samma sak händer med uthyrning av bostäder. Airbnb kommer att ha ett mycket begränsat utbud under högsäsongen – som sommaren – men ett överutbud under andra tider på året”, säger Chen. ”Sedan finns det andra faktorer. Hur lätt är det för någon att delta på marknaden? Måste man till exempel äga ett hus för att delta? Måste man skaffa en licens? Omkring 25 % av den amerikanska arbetskraften arbetar inom något licensierat yrke. Dessa faktorer kan orsaka friktion i dynamiken mellan utbud och efterfrågan.”

Läckage i accelerationshastighet för utbud och efterfrågan

Även om marknadsplatserna blir allt vanligare måste de kämpa med läckor på utbuds- och efterfrågesidan. ”Låt oss gå tillbaka till Pietra, marknadsplatsen för smycken. Det är ett bra exempel på den här dynamiken där efterfrågesidan inte nödvändigtvis köper så ofta. Visst? Förhoppningsvis köper du inte mer än en förlovningsring”, säger Chen. ”Om man ska få folk att köpa till sig själva kan det ske oftare, men det kommer förmodligen att ske i samband med ett speciellt tillfälle. Det är där du kanske upptäcker att efterfrågesidan inte är läckande, utan bara inaktiv.”

Målet är sedan att återerövra eller återaktivera dem. ”Om det verkar som om det finns en läcka på efterfrågesidan är det förmodligen okej om det bara är människor som går in och ut ur aktiviteten. Så länge verksamheten har ett bra, skalbart och billigt sätt att skaffa användare kommer det att vara okej. För vissa kan det vara genom SEO, så att människor kan hitta företaget”, säger Chen. ”På den andra sidan av ekvationen – utbudssidan – tillhandahåller du i idealfallet så mycket arbete och intäkter att de är mycket nöjda med upplägget och stannar kvar. Efter att ha tittat på många marknadsplatser genom åren har jag kommit fram till att man vill att åtminstone en sida ska vara ihållande. Det är inte alltid efterfråge- eller utbudssidan, men det måste vara en av dem vid någon tidpunkt. På så sätt kan du alltid sänka priserna på utbudssidan, vilket gör det mindre ihållande för dem, men öka användningen och frekvensen på efterfrågesidan.”

Även de mogna marknadsplatserna hittar sätt att mildra läckor i utbud och efterfrågan. ”Jag tror att under de första sju åren av Ubers existens sänktes priset varje januari. Det fanns i systemet för att motverka eventuella läckor. Den sänkningen fick marknaden att växa varje år tills vi nådde en punkt där alla var fullt mättade och sänkningen inte skulle öka användningen längre”, säger Chen. ”Så jag återvänder till Pietra med det här perspektivet i åtanke: Jag skulle inte oroa mig för att efterfrågesidan är intermittent. Det är fantastiskt om man kan komma på hur man kan vägleda människor från förlovningsringar till födelsedagar till andra typer av tillfällen att köpa smycken. Men vad jag verkligen skulle titta på är: Är juvelerarna nöjda? Hur mycket av deras verksamhet drivs av marknaden? Kan de i princip försörja sig själva genom att bara vara Pietra-deltagare? Det är det jag är mest intresserad av.”

Idéerna bakom nästa stora marknadsplats

Chen är angelägen om att se nya permutationer av marknadsplatser ta form. Här är tre idéer som han tror kommer att driva dessa nya typer av marknadsplatser framåt.

Alla kan göra något de älskar och få betalt för det: ”Idealet för samhället är att alla kan göra något som de älskar och få betalt för det. Om det handlar om att hitta en publik genom att skriva eller blogga finns Substack. Om det är att skapa, finns det Patreon. Om det handlar om att undervisa barn finns VIPKid. Om det handlar om att få ut människor i vildmarken finns Hipcamp”, säger Chen. ”De här marknadsplatserna är något helt annat än att transportera mat eller människor. Det är marknadsplatser som omdefinierar hur framtidens arbete ska se ut. Jag tror att fler av dessa branscher i slutändan kommer att bestå av en samling marknadsplatser istället för att ledas av centraliserade företag som arbetsgivare.”

_Licensiering är inte det enda sättet att säkerställa kvaliteten _ ”Licensiering var meningsfullt i en värld där regeringarna var tvungna att säkerställa kvaliteten på allt. Men det orsakar ett stort problem för en större del av vår ekonomi. Det gör det så mycket svårare för människor – särskilt timanställda – att få jobb”, säger Chen. ”En artikel nyligen i New York Times visade att många licenser, till exempel inom kosmetologi, kräver dussintals timmar i skolor och ger människor hundratusentals kronor i skuld. Sedan arbetar de på en salong och tjänar minimilön. Det är början på en kris. Det finns en möjlighet för marknadsplatser att använda programvara, betyg och recensioner för att skapa transparens, så att människor kan hitta arbete, och potentiellt kringgå den besvärliga licensieringsprocessen.”

Programvarulager för marknadsplatser sätter ribban. ”Det finns en ökning av marknadsplatser som går längre än att digitalt sammankoppla utbud och efterfrågan – de skapar aktivt förtroende mellan dem. Dessa ’hanterade marknadsplatser’ med full stack höjer proaktivt kundupplevelsen för alla delar av en marknadsplats”, säger Chen. ”Till exempel är Honor en hanterad marknadsplats för hemtjänst. De ger inte bara en lista över vårdgivare som människor kan upptäcka och anställa. Honor intervjuar och screenar varje vårdgivare innan de onboardas. De kopplar kunder till rådgivare för att utforma personliga vårdplaner. Honor har kontrollen när det gäller att definiera kundupplevelsen för varje sida av marknadsplatsen och att bygga förtroende mellan dem.”

Marknadsplatser är fullt realiserade

Chen hjälper marknadsplatser att klara av kallstartshindret, eftersom företagen då har chansen att frigöra stora möjligheter när de skalar upp. ”Uber lärde mig hur tillväxt verkligen ser ut. Under min tid där var det till stor del handlat om produkt/marknadsanpassning. Verksamheten gick snabbt – och min roll var att ta reda på hur vi skulle få den att gå ännu snabbare. Vissa veckor hade vi över 200 nya medarbetare. Vi registrerade över 3 % av världens befolkning varje år”, säger Chen. ”Men möjligheten till den här typen av tillväxt är vilande tills marknadsplatserna löser kallstartsproblemet. Det är först då som ett svänghjul blir till en vindmölla – något som kan driva och upprätthålla en verksamhet.”

Läs om hur marknadsplatser använder Stripe eller kolla in Stripe Sessions för att höra Chens partner på Andreessen Horowitz och tidigare VD för OpenTable, Jeff Jordan, tala om hur innovativa marknadsplatser skapar differentierade upplevelser för säljare.