Nobody starts a company because they love fundraising. But for many companies, accelerating a venture-scale business requires millions—or billions—of dollars worth of capital.

Unfortunately, building fundraising decks and pitching investors are not skills that founders develop before starting a company; they’re learned by doing. So first-time entrepreneurs often struggle to craft a story—their story—that will end in a term sheet.

While it’s true that every company is unique, it’s also true that every pitch has the same goal: to assure venture investors that your company has the potential to achieve a valuation over a billion dollars. Your startup may not yet generate revenue, but it must generate conviction.

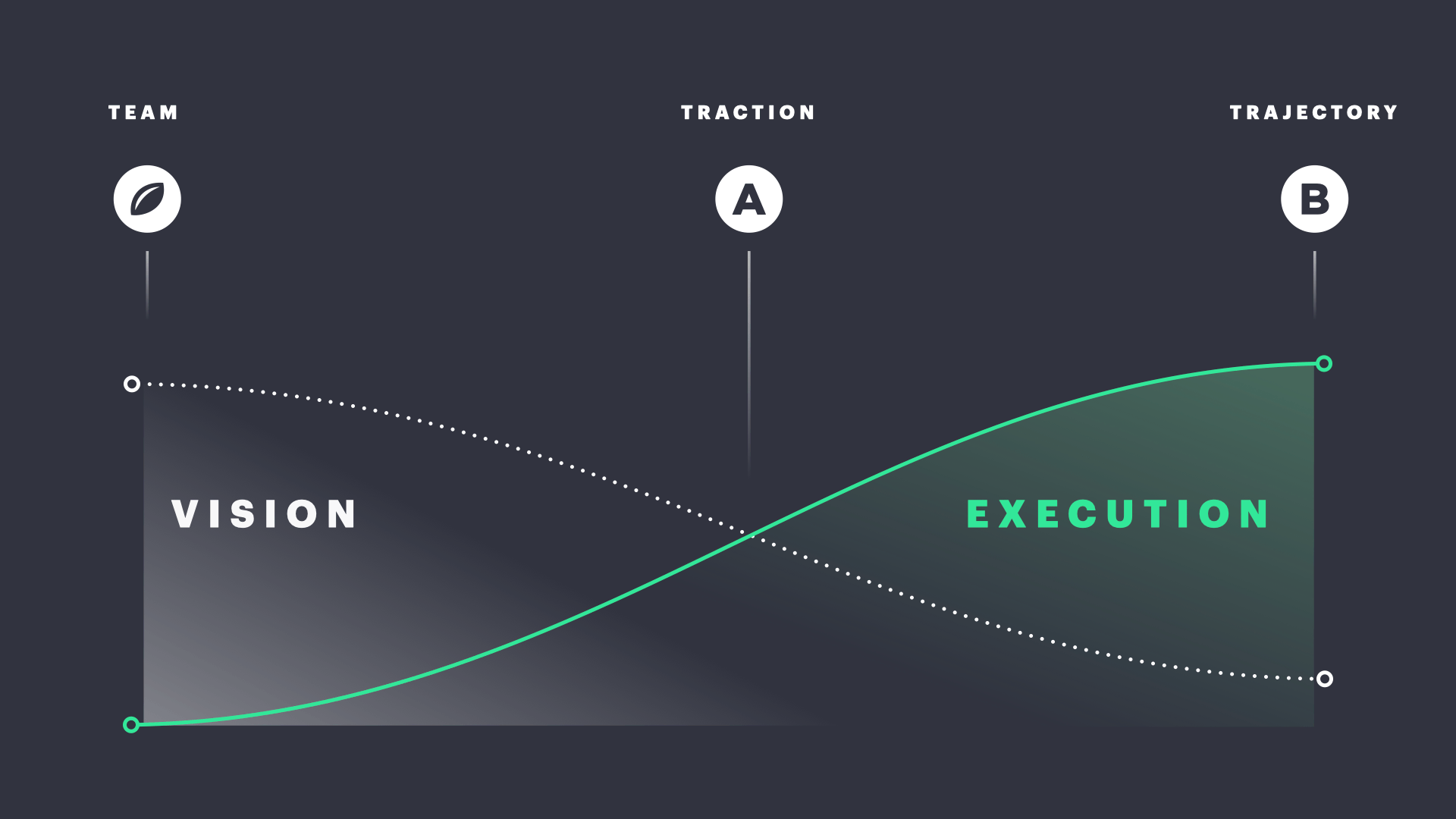

This is no small feat. It requires a leap of both reason and faith, which means that an effective pitch must instill confidence and inspire belief. An investor needs to see you are an expert in your space, a master of your own data, and the kind of storyteller who can convince customers, employees, and the next round of investors to join you on an improbable journey. Early-stage founder, this is for you. It draws from six years of building pitches that have led to $4.5B in raised capital. As you embark on raising your seed or Series A round, you’ll need to tell a story with a mix of vision and execution appropriate to your company stage. This resource will help you articulate why your company should exist—and give investors the best chance at squinting and seeing that billion-dollar outcome. Let’s begin.

Think in acts, not slides

The startup world has a lot of lore—and deep archives—on pitching. There’s commentary on early decks of now-famous companies, pattern-matching posts on pitching from venture capitalists, and presentation templates galore.

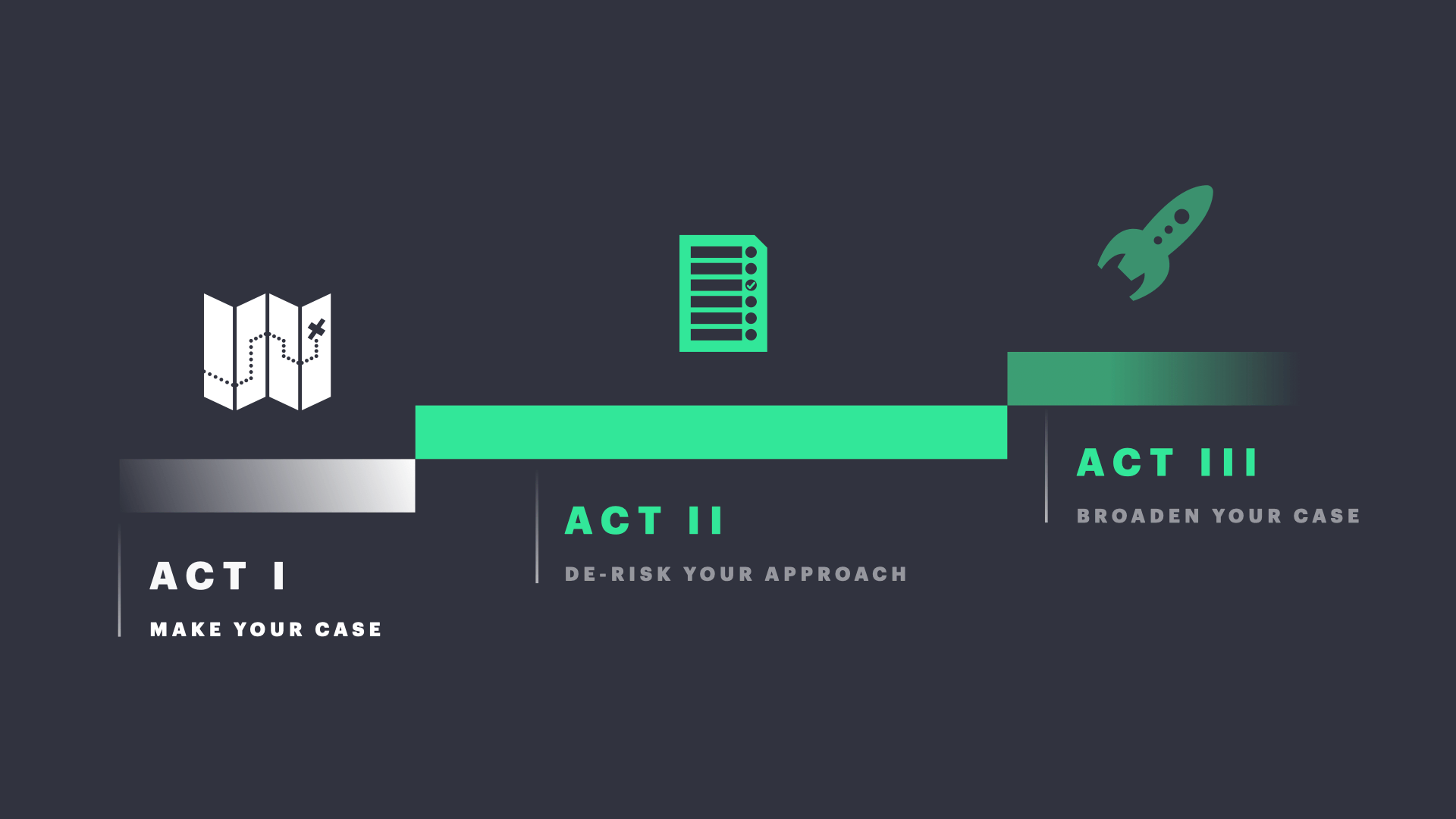

Instead of thinking in terms of slides, we recommend that you separate your pitch into three basic “acts” and work through each of them one by one. These three acts represent the essential movements of every pitch and give founders a clear sense of what needs to be proven at each stage and how to prove it.

The three acts are as follows:

- Act I: Make your case. What are you building? What can it become? Why now? Why you?

- Act II: De-risk your approach. What have you done to increase your odds of success?

- Act III: Broaden your case. What does success mean to you, your investors, and the world?

In this guide, we’ll focus on the first act. This is where founders set the tone of the pitch and the framing for everything that follows, whereas the second and third acts lean into company-specific proof points. The first act is where we dedicate most of our time with founders—we find that we spend over half of our time crafting and refining the first few slides of the pitch. It’s that important.

The first act and its pitch plots

Your deck’s first act—or first few slides—must hook an investor. There’s a misconception that you must follow a strict sequence of slides to make a compelling case. In fact, the first act of a pitch can contain any combination of slides, as long as it communicates your:

- Unique understanding of your market

- Key insight into that market

- Unique product or service

- Signal that your approach is working

That’s a lot of impression to make and information to convey over your opening slides, let alone an entire deck. The first act does the heavy lifting, and it must do so efficiently. Over the years, we’ve noticed some recurring narratives when producing strong first acts. We call these pitch “plots”—or frameworks to organize your story. Choosing the right pitch plot is a critical first step.

The five most common pitch plots

Most early-stage startups map to one of five pitch plots. Each has a similar structure:

- The beats are the parts of a story that build on each other to form a plot. A good rule of thumb is to allocate one slide—and a minute or less of speaking—per beat.

- The sample deck in each section illustrates how the beats connect and how each pitch plot might look in the wild.

- The field notes are our top observations on each pitch plot—namely where they’ve worked best and fallen short for founders and companies.

A final, important note: There is not one plot that works best—they’ve all worked with investors. Before you pitch, experiment with different pitch plots to find the one that allows you to authentically explain the best, most resonant case for your opportunity.

🔄 Starting over

Many investors like to make bold bets—few wagers are more daring than reinventing a market from the ground up. Think Tesla or Ethos. Or perhaps economist Joseph Schumpeter, as this plot unleashes the “gale of creative destruction” through which an industry evolves by leveling and recreating itself.

The beats

“This is the mess that is our market today…”

The idea here is to paint a picture of a market, an industry, or a workflow that is stuck in the past. Maybe it’s still mired in paperwork. It might involve hours of manual work that could be completed in seconds with automation. Maybe the software hasn’t gotten better since 1980. Or it simply hasn’t taken off. Your goal is to make the audience feel this criminal level of inertia—whether it’s with statistics, images, or a powerful anecdote.

“Here is how it got there…”

Educate your audience. Help them to understand why the market looks the way it does. Is it dominated by incumbents with no incentive—or ability—to innovate? Is there a historical reason why it had to be the way it is, but no longer does? Has there been a big technological challenge that is yet to be solved? Whatever the answer, it should neatly set the stage for the key insight you’re about to unveil.

“What if we could start over from scratch?”

Wipe the slate clean and show how your company has a distinct advantage precisely because you are a new entrant. Show the investor how this market might be rebuilt if a founder didn’t have the baggage of being an incumbent, the burden of history, or lack of available technology. Make the solution seem simple, straightforward, and inevitable.

"That’s what we’ve done…"

Contrast your solution to the mess you described earlier. Walk your audience through how your product works, with a focus on the tangible differences that result from starting from scratch: Is it faster, cheaper, more delightful, less onerous, or simply better than what’s out there?

The sample deck

The field notes

When it works. This plot works best if you are educating investors on a market that’s unfamiliar to them. It allows you to demonstrate expertise and gives your investors the freedom to evaluate your business in a vacuum. If you can convince an investor that your company is the only one taking your approach, then you are the only founder who matters.

Use caution. Avoid “educating” an investor with a story they already know. If you don’t know what an interested observer of your field definitely knows, you don’t know your field. And worse yet, it’s a negative signal. For example, don’t hinge your pitch to fintech investors on the challenges of the unbanked. They’ve almost certainly heard (and probably have funded) that pitch. The last thing you want is to get caught in a ten-minute debate on the first slide—or worse yet, generate knowing nods and blank stares. It’s also important to consider what it is about your approach that makes it unique. For example, if what sets you apart is your marketing strategy—as opposed to something more defensible—it might be hard to argue that you are fundamentally reimagining your market, and your pitch might seem like an overreach.

⬇️ Doing that over here

A precise and powerful analogy goes a long way, especially when your analogs are valued in the $1B+ range. Early-stage versions of Catch (“Gusto for freelancers”) or BallerTV (“ESPN for amateur sports”) would’ve been good candidates for this plot. This is a particularly useful choice when your investors are not already intimately familiar with your market.

The beats

“Look at this other market (or these other markets) that have evolved…”

Big waves move all boats, so if you see other major markets transformed by a trend, plausibly that trend will arrive in your market soon. In the past, these forces might have been mobility, the cloud, or the internet of things. Today, they’re more likely to be artificial intelligence, real-time decisioning, or any number of trends that are reshaping markets. These examples are powerful, because they prime your approach before you introduce it.

“Our market has been left behind…”

Next, draw a sharp contrast between these markets and yours by explaining how your market works today. Focus on the pain points created by these forces not being reflected. If done well, you’ll create a sense of inevitability. Nature abhors a vacuum.

“It would look like this…”

This is your chance to pay off the analogy. Paint a picture of what your market would look like if it met the modern standard. Take your audience step-by-step through a transformed experience and its implications for users, for your industry, and for the company that can deliver that experience.

“This is exactly what we are building…”

Present your company as the agent of change between where the market is today and the perfect world that you’ve just laid out. Explain what you’ve already accomplished to put you on that path and what remains to be done. The idea is to show, simply and clearly, that you are on course to realize that vision.

The sample deck

The field notes

When it works. This plot is entirely dependent on the size of the gap between where your market is and what it should, would, or could be with the right technology. It is also particularly effective if you can distill what makes you unique down to a single technology or business model (e.g., artificial intelligence, SaaS, etc.) so that the link to other markets is extremely clear.

Use caution. Pressure test every aspect of the analogy to make sure it’s airtight. If there is any inconsistency between your market and its analog, investors will start poking holes. The fewer variables between the two markets the better. The last thing you want to do is to get dragged into an argument about a market that you don’t even operate in. Plus, there’s a good chance investors have spent time—and capital—getting smart on your analog markets.

💡 But here’s the thing…

This is less of a plot than it is a rhetorical device, but it can be an incredibly effective way to open a pitch. If your goal is to convince an investor that you are the best person to solve a problem, then the best thing you can do is demonstrate that you understand the problem better than anyone else. For example, this plot might be a nice fit for Rahul Vohra of email service Superhuman. He has spent over a decade reimagining email as a founder (Rapportive, Superhuman), investor (sendwithus), and advisor (InboxVudu).

The beats

“Insiders in our market know that…”

Open with an interesting fact or statistic that an investor doesn’t already know and likely wouldn’t find in her cursory research before your meeting. Ideally, this statistic is unexpected, counterintuitive, or just plain interesting. But, most importantly, it should set up the next beat of your story.

“But here’s the thing…”

Introduce your unique insight here. If it’s an observation that insiders know, then your insight should offer a perspective that is exclusively yours. The idea is to go one level deeper than your opening fact or statistic to reveal a hidden truth about your market. For example, if your interesting fact is that your market is growing incredibly quickly, then your insight might be that the market is still significantly smaller than it should be.

“This opens the door to a massive opportunity…”

The next step is to connect your unique insight to the business opportunity in front of you. The implication is that armed with your unique insight you can build a specific kind of company that is unlike anything else in the market. For example, if your market is massively underpenetrated, you might focus on the fact that you’re building a product that won’t immediately compete with incumbents, because it serves a hidden market that is adjacent to the current market.

“We are built for this…”

Introduce your business in this context. Explain clearly how everything about your company—from the product to the go to market—has been designed to exploit this unique insight.

The sample deck

The field notes

When it works. This is a challenging plot to pull off because it requires you to present both (1) a fact or statistic that your audience doesn’t already know and (2) an insight that feels fresh and original. As a result, this tactic works best when you have a significant information advantage over the investor, which means that founders who have worked in the industry and establish credibility often have the most success.

Use caution. If either your “interesting fact” or your “unique insight” are already familiar to your audience—or if they are intuitive to most people—this opening will fall flat, and your rigor or credibility may be in question. Once you’ve settled on the stats and insights that you plan to share, first validate that they’re truly unique. Run them by colleagues, industry insiders, and friendly investors. If you’re not impressing them with your originality, you likely won’t impress investors either.

📱 All the kids are doing it

One of the biggest challenges in any pitch is demonstrating differentiation. To do so, show how your offering is sparking undeniably new customer behavior or uniquely benefiting from it. This plot might be the first choice for an earlier-stage GitHub or Figma.

The beats

“There is a big shift in behavior underway…”

This plot opens with an underlying trend that sets the foundation for your company—but not the trends you see in every other pitch. You need to give a sense that you have uncovered a trend, not just read about it. So avoid Gartner studies and consumer surveys and look for data or anecdotes that reveal a trend that is hidden in plain sight. Imagine Airbnb in its earliest days pointing to the emergence of temporary housing listings on sites like Craigslist as evidence that people were interested in non-hotel accommodations.

“The incumbents aren’t ready for it…”

If you’ve effectively demonstrated that a trend is real, then your next task is to show that the incumbents either don’t see it or can’t move fast enough to respond to it. Illustrate the clash between the expectations of the user and what the incumbents offer.

“We saw it coming…”

Leverage your origin story to illustrate founder/market fit. Show that you’re at the cusp of the opportunity that you’ve prepared for for years, not because of an accident but because you’ve been planning it. Show how your company was built with a deep understanding of this trend, and how this has translated to your approach to product development, go to market, team building, and more.

“We built a company for this new world…”

Provide early evidence that you are benefiting from this trend. This could be early traction, customer testimonials, or any other indication that you are resonating with early adopters. Give investors a sense that you’ve discovered the inevitable.

The sample deck

The field notes

When it works. If your company is on the forefront of an emerging trend that others are not yet seeing, this can be a powerful plot. The Airbnb example is an instructive one. Ideally, the trend you’re identifying can only be found if you look deep inside the data. It should be something that only you were looking for—and found. Epoch-making insights are probably not available via a Google search; show you won the knowledge.

Use caution. Investors are looking for long-term trends that transform markets, not temporary blips. In recent months, we’ve seen pitch after pitch leverage COVID-19 as the tipping point for their market or their product. But is the change you’re seeing likely to outlast the pandemic? And if so, how can you make that clear to an investor?

✋ I took it personally

Investors are looking for founders who dedicate their lives to solving a problem, which means it’s incredibly powerful if you can speak to how that problem has impacted you personally. For example, this plot could have been used by John Crowley. When two of his kids were diagnosed with Pompe disease, Crowley left a career in finance to develop treatments for people with rare diseases and few options. Driven to help his children, he’s spent decades working at and founding biotech and pharmaceutical companies. He now leads Amicus Therapeutics, which discovers, develops, and delivers medicine for people living with rare metabolic diseases.

The beats

“Let me tell you about a time when I tried/had to…”

Share your personal story of struggle. This can be a “fish out of water” story in which you—as an outsider—tried something for the first time (e.g., applying for a mortgage). Or it can be an “inside baseball” story in which you struggled with a problem that has long plagued members of your community of practice (e.g., manually reviewing mortgage applications).

“It was an awful experience…”

Summarize the story by distilling the two to three fundamental barriers that stood in the way of making this process as seamless, intuitive, simple, or effective as it could be. This is where you set up the problems that you had to believe you could solve before starting your company.

“I did my research…”

Walk through the steps you took to better understand this problem. Who did you talk to? What did you learn about the size and scope of this problem? How long did you spend iterating on your idea? Who were you able to recruit to help you take on this challenge? These are the stories that resonate with investors and give them the confidence that you are committed to solving the problem in front of you.

“I built the solution that I would want…”

Illustrate how your product solves the problem that you were facing. But quickly transition to the value that your product can bring to the market at large. This is your chance to demonstrate that in solving a problem for yourself you uncovered a massive business opportunity.

The sample deck

The field notes

When it works. We only recommend this plot to founders with an authentic story to tell. Investors are bored to tears by founders forcing themselves in as the hero of the story. But if your origin story is core to the narrative you share with customers or employees, it’s a good indication that it will resonate with investors as well.

Use caution. Even if your story is authentic, it only works if it’s relatable. It’s not necessary for investors to have experienced the problem themselves, but they should be able to put themselves in your shoes. If a problem is complex or esoteric—or feels like a “nice to have” versus a “must have”—a personal story can not only lose its momentum but also its currency.

The plots thicken

Once you’ve chosen your pitch plot, you’ve taken a significant step in defining your fundraising presentation. Stay the course on your deck and build out the second and third act of your pitch. If you need help, watch the recording of our AMA, where we go into more depth on fundraising pitches. Learn more about 4th & King and reach us at: hello@4thandking.com

Stripe Atlas has additional resources to help with your fundraising. Read more on pitching your early-stage startup. To stay current on similar guides for startups or if you have any thoughts about what other guides would be useful to your online business, please write us at: atlas@stripe.com